Deep Map of The Potteries

Whilst studying Archaeology and Anthropology at the turn of the century I was introduced to the concept of a Deep Map. This is a map that is more than a two dimensional representation of the physical features of a landscape. A map that explores every aspect of the human environment; emotional, creative, modern, historical, physical, spiritual. Anything and everything that can be experienced within a landscape.

“Reflecting eighteenth century antiquarian approaches to place, which included history, folklore, natural history and hearsay, the deep map attempts to record and represent the grain and patina of place through juxtapositions and interpenetrations of the historical and the contemporary, the political and the poetic, the discursive and the sensual; the conflation of oral testimony, anthology, memoir, biography, natural history and everything you might ever want to say about a place…” Mike Pearson and Michael Shanks, Theatre/Archaeology (Routledge 2001)

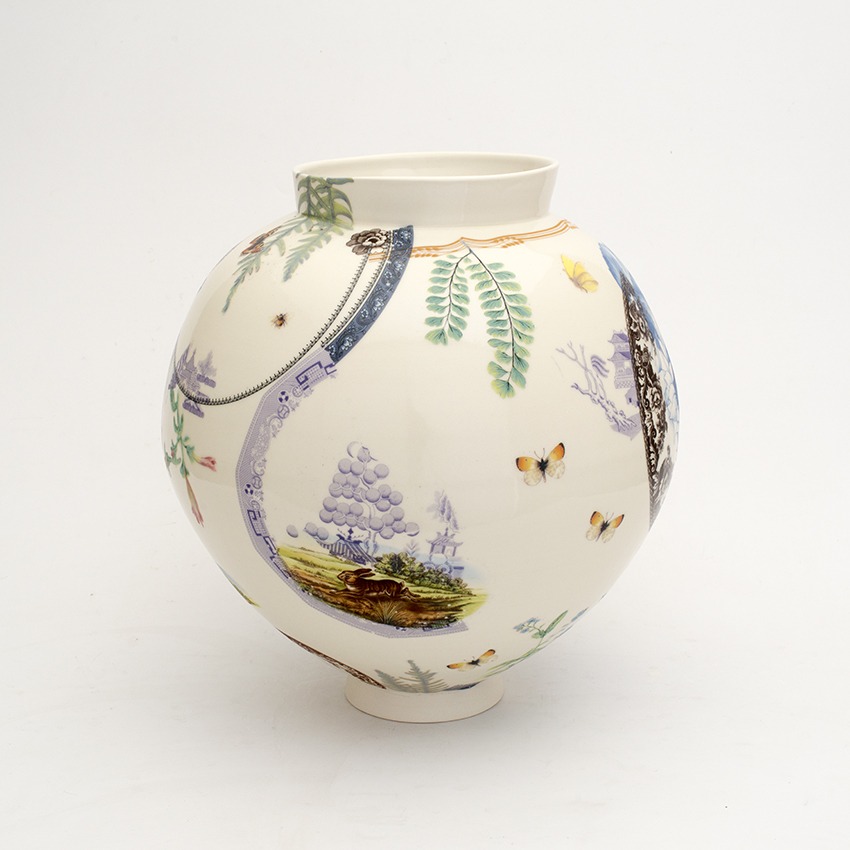

My work uses a single pure jar form as a canvas to map my observations from an ongoing study of my surroundings. I am particularly interested in the human experience of landscape. The acts carried out within a landscape, for example those associated with resource collection, shape our understanding and perception of the world around us. I source materials that can be incorporated into my work, digging clay from the moors and stone from coastal outcrops. I do this partly for the aesthetic values it brings to my work but also as an act within the landscape that creates a narrative, one that conveys a unique sense of place.

This is the basis of all my work to date and is mostly centred on the landscape in which I live and work, Pembrokeshire. For this year’s British Ceramics Biennial I have taken this methodology and applied it to an entirely new landscape, that of Stoke-on-Trent, focussing particularly on the present and historical activities of the pottery industry.

My hope is that by incorporating actual parts of the Stoke landscape including natural, urban and industrial materials the viewer will get a feeling for Stoke as a place. Translating a feeling for a place through any medium is complex. Each piece here is a personal interpretation of the experiences I had while visiting Stoke-on-Trent. Walking around, talking to people, touring many of the existing potteries and suppliers, looking, hearing, sensing the environment around me. One evening whilst walking to a restaurant for dinner I passed the diggings of house foundations, pottery shards covered the disturbed earth. Salt glazed, brick, tile, willow ware, purple glazed foot rings, greens, yellows, all there in the earth. Not rare but everywhere like aggregate in the soil. Not precious either, most likely spoils from the nearest pot bank. Precious though as they bring you back to the hand, the hand or hands that created all those pieces that didn’t make it through the kilns. It is actually quite staggering when you think about the amount of ceramics produced in the city for the earth to be full of waste pottery. The efforts of generations of skilled workers and their families beneath the feet of today’s residents.

Stoke-on-Trent feels deprived yet vibrant, alive yet nostalgic. The nostalgia is justified because what has gone on in the city is quite extraordinary. The humble exterior belies generations of immense skill, creativity and artistry. Out of the dirt, the coal, the hard labor comes some of the most refined and highly decorative china the world has ever seen. It shows that humans are artistic, this was not a special work force that created the wares of the potteries. They are everyday people tasked with jobs that required artistry and skill. Residents in touch with their creative nature and a sense for the innate skill within their hands.

The city is built on two key resources, clay and coal. Contrary to what you may think the potteries are founded here more because of the coal than the clay. The two are intrinsically linked geologically as clay is often the bed of coal. Although the clay is good and still used to this day it is not versatile enough for the array of different wares that Stoke has produced. Coal however fired virtually everything until the Clean Air Act of 1956.

Coal is a beautiful material, jet black and often shiny like a piece of obsidian, I remember marveling at it as a child. Formed from flora of the vast swamp forests of the Jurassic the plants laid to rest on the clay beds of the lagoons. It has provided us with so much but at a cost that was at first unforeseen and now seems almost unthinkable. Rarely seen these days it is a reminder that moderation and consideration are important.

One thing that the local clay has been used for throughout the history of pottery production is bricks. They are fundamental to the built environment of the area and to the creation of the ceramic wares for which it is so famous. They also connect directly to the earth beneath the six towns. Tunstall, Burslem, Hanley, Stoke, Fenton and Longton were amalgamated into one city in 1910. The towns follow the clay and coal seams from Tunstall in the north to Longton in the south.

Clay dug straight from the ground, has always been integral to my work. It was important for me to source clay from beneath the city. The hue of baked earth, so basic in its origins and so synonymous with the buildings of Stoke. The unglazed surface of Etruria Marl acts as a humble representation of what the city is built on and of. This basic red clay used to build the kilns that created the refined white porcelains and bone china. A clay essential in the creation of the wares but rarely in its own right as a piece of pottery.

Stoke-on-Trent is synonymous with bone china and so I wanted to create a piece using this rather macabre clay body. Cattle bones make up almost half of the clay. Developed by Josiah Spode in the 1790’s as an attempt to emulate the fine porcelains imported from China, this very strong, white and translucent clay surpassed porcelain in many aspects. To a thrower bone china is a strange substance; short and crumbly it lacks the plasticity to be formed on the wheel.

My other immediate association with the wares of Stoke are the decorative ceramic transfers developed as a more affordable method to meet the increasing demand for delicate fine bone china. Once again Spode was key in the development of transfers. Looking around the old works off Elenora Street I was shown a heap of left over transfers, some of which have been used in this installation.

Certain materials are essential to the creation of pottery, most of which do not exist in Staffordshire. These had to be brought to Stoke; fine clays from Cornwall, flint and ball clays from Dorset as well as many other materials from all over the country. The finished wares also had to be transported out and this was problematic until the canals were built. Walking along those canals today their significance is very apparent.

Paths are a motif I have used to represent my actual and metaphorical journeys through a place. To understand a landscape is to move through it, to give it context. Paths are like common routes of experience, guiding us through the landscape. They are connections through time, to others and to the land.

With this in mind I wanted to depict the two Canals that pass through the city. Jasper ware, with its small relief narratives seemed an opportunity to portray a different narrative, that of the canals. The Jasper Ware tradition has been an influence on my work for some time. I created my own coloured body in 2010, a dark slate blue. Josiah Wedgwood also has a strong connection to both Jasper Ware and the Canals being instrumental in their creation.

People and landscape are often seen as separate but few landscapes are devoid of people and none are unaffected by them, especially in these times. Cityscapes certainly cannot be untangled from people and stories.

It recently came to my attention that cassette tapes are coated with magnetic particles that realign in the recording process to create the sound. Iron oxide is the most common coating and it is also a very common pigment in glazes. I immediately thought of using recordings in my glazes as a physical representation of an oral event. I recorded a number of oral histories during my visits to Stoke-on-Trent wrapping the tape around a pot and firing those memories, thoughts and feeling into the glaze.

“I was born in 1955. Stayed local, Bucknell, which is only 10 minutes away from Stoke town itself, local schools … I’ve never really moved out of the area, you know. Even when I got married and started my own family, I only moved 10 mins up the road from where my Mum & Dad lived. My Mum & Dad have long gone, bless em.

My dad was a dipper for Wedgwoods and my mother was a flower maker for Doulton, you know the small ceramic flowers. My Dad had sort of like hooks which he had to put over his fingers and dip the pots in the glaze and put them on the stacks… it was constant work for him and yes, he sort of retired and lived his life out, he enjoyed it, same with me mum.

I left school in 1970 and I had a choice of three jobs. I could either go into the pottery industry and follow in my Mum & Dad’s footsteps. I could join the Parks as a gardener or British railways, you know. Well, the love of trains for me did it, so I joined. I got a job as messenger boy, £7 a week and I suppose back in those days 1970 it was not a bad wage at all, and then I worked my way up to working on the platform and from that I used to announce trains in. The big trains you know, Manchester London trains, back in the day, you would hear my voice over Stoke station.”

“I was brought up in Stoke and my mum tells a story about when she was young, that clay and ceramics was a massive part of her play time. The boys used to run off to the marl holes and there was obviously a certain place where my mum used to go and the girls would run off to what she calls ‘white tips’

It was all the ware that the factories didn’t want and they were massive. They would clamber over all of the ceramic ware and salvage things, then role play with them. They would play tea parties or have a princess feast or something like that. Then she would take them home and my nan would go mad because she didn’t need any more pots.

My Nan was a dinner lady but she had previously worked in one of the ceramic factories in the kitchens. My Auntie’s a paintress for Wedgwood and still is. Everyone is associated, I mean they call it like the pits and pots, don’t they. Even now you look at the industry and you go from one town to another, a lot of them are linked to pottery, so I think it’s still a massive part of what the city is and how its defined”